London has no shortage of museums, galleries and sites of interest for the tourist, but there are many lesser known haunts that are well worth seeking out if you really want to experience a significant if little known part of this city’s colourful past. These are those little gems that are only familiar to the locals and are entirely missed by the hordes of tourists who visit London every year.

1The Clink

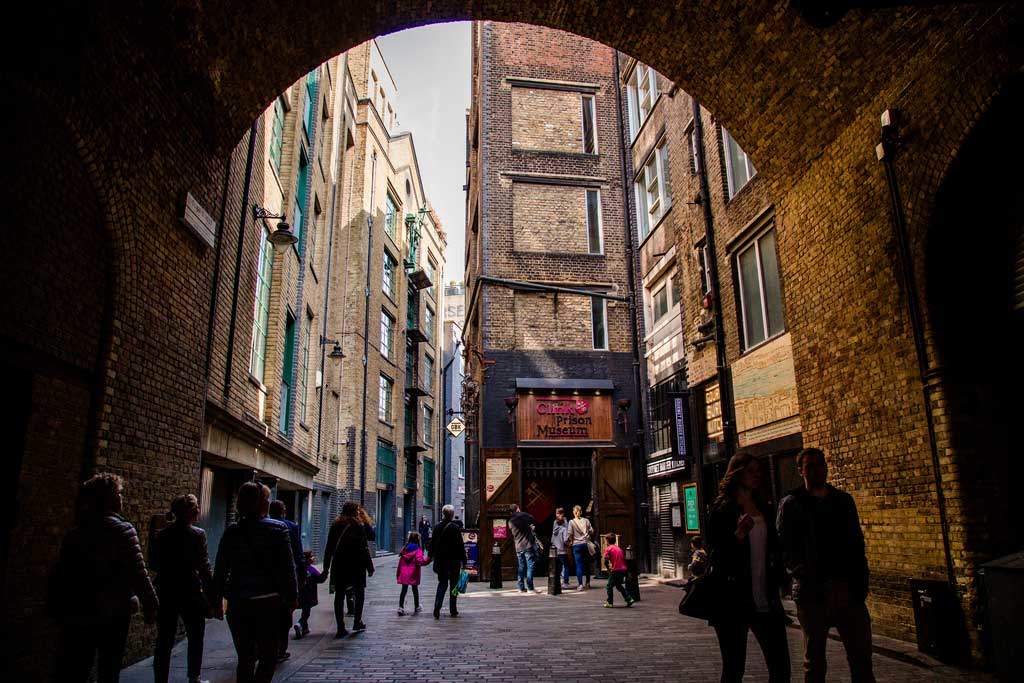

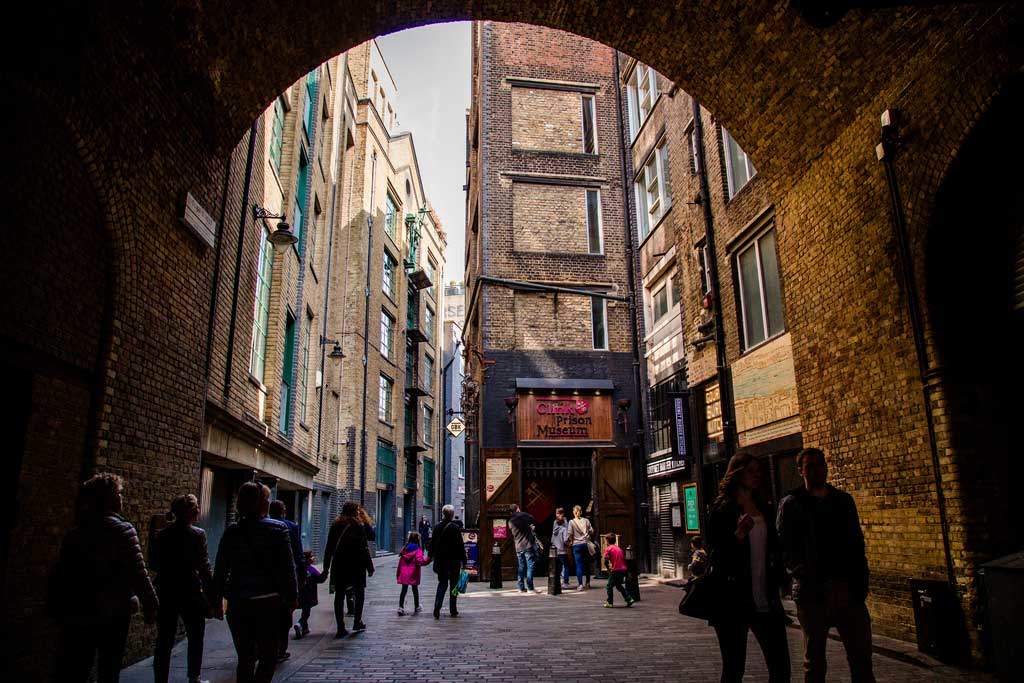

Ignore the popular and sensationalist London Dungeon which is no more than a gory Madame Tussauds and instead, head for The Clink Museum nearby in Clink Street. This small establishment is built on the original site of London’s oldest prison. Known as The Clink, this dubious establishment began life way back in 1144. At that time the area was known for its brothels, bars, bull-baiting and theatres, and The Clink, which was owned by the Bishop of Winchester, was London’s attempt to curb the local excesses.

Originally there were two prisons here: one for men and the other for women. And the Clink would undoubtedly have provided the bishop with a very satisfactory income from regulating the brothels and the resulting fines and prison sentences meted out. Indeed, the brothels were closed, reopened and moved over the years, and brought a constant stream of prisoners to the Clink’s doors.

By and large, prisoners were appallingly treated by their gaolers, who were themselves very poorly paid. Though if you or your associates outside had money, you could pay the gaolers to make your stay here more bearable. So to supplement their income, gaolers would hire out rooms, bedding and candles. They’d even accept payments for fitting lighter irons or removing them altogether. If you were unfortunate enough to be one of the penniless prisoners, you’d have to beg and sell anything you possessed including your clothes just to pay for food.

Here you’ll learn much about the area’s history and have the opportunity to handle original artefacts including some fairly questionable torture devices.

There is also a rather spooky side to the museum, as there have been an unusually high number of reported paranormal incidents occurring on the premises. These have ranged from the sighting of figures walking through walls to doors opening and closing and glasses inexplicably smashing. Who knows? You may come closer to history than you were anticipating.

No visit to London would be complete without a visit to this unique and fascinating museum.

[irp posts=”790″ name=”Top 10 Sehenswürdigkeiten in London”]2The Cheshire Cheese public house

While Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese public house at 145 Fleet Street may not be the oldest pub in London, there has been a pub on this site since 1538. During the Great Fire of London in 1666 the pub was burnt down but rebuilt shortly afterwards. Unlike other pubs which survived the fire because they were built from stone, this one was constructed primarily from wood. However, much of its internal wood panelling today is almost certainly 19th century though its vaulted cellars are thought to have belonged to a 13th century Carmelite monastery.

Despite its lack of natural light, the pub has a great deal of natural charm, which is enhanced further during the winter months by a roaring open fire.

Needless to say, the Cheshire Cheese has countless literary associations. Among its regulars have been such esteemed luminaries as Oliver Goldsmith, Mark Twain, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, G.K.Chesterton, Dr Samuel Johnson and Charles Dickens. Dickens, in fact, alludes to the pub in A tale of Two Cities when his character Charles Darnay is taken for a meal in Fleet Street and led “up a covered way, into a tavern… where Charles Darnay was soon recruiting his strength with a good plain dinner and good wine.”

In 1890 a group of London based poets – the Rhymers Club founded by W.B.Yeats and Ernest Rhys used the Cheshire Cheese as a regular dining club from which they produced two anthologies of poems in 1892 and 1894.

If you appreciate your English literature, come here and soak up the atmosphere. While you’re at it, order yourself a well-deserved pint.

3The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

Located high up in the garret of St Thomas’s Church is one of the oldest surviving operating theatres beautifully preserved as a museum. There isn’t much known about the origins of the operating theatre other than the fact that in 1820 a herb garret was installed here on the original site of St Thomas’ Hospital. It is believed that the garret was used by the hospital’s apothecary to store medicinal herbs, and the following year a section of the herb garret was converted into an operating theatre. The original female surgical ward at St Thomas’ Hospital was situated adjacent to the herb garret in the building next-door – hence this rather bizarre and lofty location.

Before this time, operations would have been carried out on the ward. Quite what other patients might have made of this, one can only surmise. The patients here would all have been women. They would also have been poor. The wealthy were operated on at home – often on the kitchen table. In those days, surgeons had little in the way to dull a patient’s pain besides alcohol, opiates, and later on, ether and chloroform. Otherwise the surgeon relied entirely on his swift technique. Good surgeons would have carried out amputations in less than a minute.

The seating around the theatre would have been occupied by students. Being on public display may not have been dignified for the poor patients but it was the only way to receive treatment from some of London’s finest surgeons without having to pay for it. This said, many paid for it with their life, since there was no real understanding of infections and an alarming lack of hygiene. Many, of course, also died simply from the shock and trauma.

It wasn’t until 1859 when Florence Nightingale set up her nursing school at St Thomas’ that she persuaded the powers to be to move the hospital to a new site and sell the land to the Charing Cross Railway Company. So in 1862 the hospital moved to its current site at Lambeth and the operating theatre was closed up and forgotten about until 1957 when builders discovered it by chance when carrying out work to the eaves.

Besides seeing this fascinating operating theatre as it would have looked in its heyday, you can also browse the herb garret where herbs would have been stored and cured by the hospital’s apothecary. And if you’re not too squeamish, examine the fascinating display of

gruesome medical instruments employed in the days before real scientific knowledge. The Old Operating Theatre and Herb Garret can be found at 9 Saint Thomas Street, Southwark SE1 9RY.

4Keats House

The poet, John Keats lived at this charming Regency house in the leafy and salubrious London suburb of Hampstead from 1818 to 1820. It is where he penned perhaps his most famous and well-loved poem ‘Ode to a Nightingale’. It is also here that he fell desperately in love with Fanny Brawne, the girl next door. In 1820, due to ill health, Keats was advised to recuperate in Italy. Tragically, he was never to return to his beloved Hampstead and Fanny Brawne. Instead his health took a drastic turn for the worse in Rome where he died at the tender age of just 25 from tuberculosis.

Today Keats House is a small museum dedicated to the works of John Keats as well as poetry in general. Thanks to a Lottery Heritage Grant, the house has been very sensitively restored, and much care has been taken to refurbish the property to the reflect as closely as possible the way it would have appeared when Keats lived here. Alongside the house, the garden has also been replanted and designed to reflect the Regency period. There is, however, one specimen that has remained in place: a mulberry tree, which is thought to date back to the 17th century, so Keats would almost certainly have seen it.

Born in 1795, John Keats was writing poetry from the age of 18. But it was his friend, Charles Cowden Clarke who persuaded him to abandon his profession as an apothecary surgeon and pursue his natural talent. Influenced by Shakespeare and Milton, Keats was to become one of the most prominent poets of the English Romantic movement alongside Byron and Shelley.

Among the artefacts on display in the house are the engagement ring that Keats offered Fanny Brawne and his death mask.

Come here with a copy of John Keats’ poems, take in the house and garden, and prepare to be moved.

1The Secret Garden, Regents Park

Otherwise known as the Garden of St John’s Lodge, this little piece of manicured tranquillity is well worth seeking out. Its whereabouts isn’t widely known since its presence isn’t well advertised – hence the moniker: Secret Garden.

Head for the Inner Circle and its junction with Chester Road. The entrance, which is discreet (so keep your eyes peeled), leads you through a pergola walk which in turn brings you out into a lovely circular garden, the focus point of which is a large pond with the statues of Hylas and the Nymph. To your left is a glorious sunken lawn spread out before the splendid facade of St John’s Lodge. To the right is an arbour; step through this and you’ll discover the secluded oval garden in which you may care to take a seat. From here you can wander into yet another spherical garden though this one with its circle of lime trees around a stone urn is somewhat smaller.

These well tended gardens are a delight, and what makes them extra special is the fact that they are tucked away and out of sight. So on those balmy summer afternoons when Regents Park can be heaving with families, you can slip through the pergola and have this corner of paradise to yourself.

St John’s Lodge was built in 1819 and was privately owned up until 1916 when it was used as a hospital and later by the London University. Today St John’s Lodge is a private residence owned by the Sultan of Brunei.

The gardens were laid out in 1888 by Robert Weir Schultz for the 3rd Marquess of Bute and remain pretty much as they were then.

6The Soane Museum

Sir John Soane was a neo-classical architect with a remarkable penchant for acquiring paintings, drawings and antiquities on a mind-boggling scale. Indeed, his collection grew so incredibly large that he had to purchase several houses next door to accommodate his treasures. He began at number 12 Lincoln’s Inn Field in 1792. By 1806 he had bought number 13 next door. And by 1823 he had purchased number 14. During Soane’s lifetime, the house was established as a museum by a Private Act of Parliament.

Sadly, this became a legal necessity because Sir John’s legal heir, his son George, was by all accounts a thoroughly unpleasant character who refused to work, was constantly in debt and had written scathing pieces about his own father in the Sunday newspapers. So to stop his son laying claim to his property following his death, Soane senior set about disinheriting his son via a private Act in order to “reverse the fundamental laws of hereditary succession.”

As Soane’s business and personal wealth grew, he was able to purchase items that would have been at home in the British Museum. Such pieces include the alabaster Egyptian sarcophagus of Seti I, which he bought in 1824 for the princely sum of £2,000. Once the piece had been installed, Soane threw a three day party for 890 guests, including the Prime Minister, Robert Jenkinson, Robert Peel and the artist J.M.W. Turner. Other fascinating exhibits of ancient antiquity to be seen here include Greek and Roman bronzes, mosaics, vases and Roman glass.

In addition to the antiquities are the countless plaster models of statues and the paintings including four by Canaletto, twelve by Hogarth, one by Watteau, three by his good friend J. M. W. Turner, and one by Joshua Reynolds.

Then, of course, there is his own personal legacy: his extraordinary body of work represented by no fewer than 30,000 architectural drawings and 251 architectural models. Most of the drawings have been bound into 37 handsome volumes, and the remainder have been framed and adorn the walls. 118 of the models are for Soane’s own buildings; 44 of which relate to his work for the Bank of England.

What makes this museum so unique is the fact that it isn’t a museum in the conventional sense. This is first and foremost a home in which its remarkable owner was able to indulge his passion for collecting. The rooms, which are fascinating and impressive in themselves, tell us much more about Sir John Soane than any dry text could possibly attempt.

For anyone with an interest in art, architecture and civilization, this place is a must, but be warned, once through these doors you could well find yourself spending a great deal longer here than you might have expected. Such is the draw of the place.

7Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Lincoln’s Inn

Step out of the Soane Museum back into Lincoln’s Inn Fields. This is London’s largest public square and was originally laid out in the 1630s. It takes its name from the inns of court next door and the oldest building to be found here is Lindsey House occupying number 59-60, which dates back to 1640 and was designed by Inigo Jones. Its close proximity to Linclon’s Inn has over the centuries attracted several law firms to ply their trade here. The solicitors Farrer & Co set up their business in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1790 and remain here to this day. Among their prestigious clients is Queen Elizabeth II.

Make your way through to Lincloln’s Inn and you’ll be entering a world that will appear Dickensian. Established way back in 1489, this became the seat of legal learning. Today there are in fact four inns of court in London from which barristers practise. Lincoln’s Inn is arguably the most attractive and interesting of them all. Indeed, besides being able to spot barristers in their natural setting sporting their archaic wigs and gowns, you may very well spot a film crew filming a period piece or an English legal drama amid these attractively cobbled streets.

Lincoln’s Inn comprises three exquisite squares, the Old Hall, dating back to 1489, the Chapel, the Great Hall and Library, and the Gatehouse, which dates back to 1521.

Lincoln’s Inn is situated in Holborn, across the road from the Royal Courts of Justice. The nearest tube station is Chancery Lane.

8The Phoenix Cinema, East Finchley

The Phoenix Cinema is London’s oldest working cinema. Built in 1910, it opened its doors in 1912 as the East Finchley Picturedrome. The first film to be screened here was a documentary about the ill-fated Titanic which had sunk that very same year. Having changed hands and undergone various architectural changes over the years, its unique barrel vaulted ceiling has remained intact along with its 1938 Art Deco panels. Its patrons include film directors Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, writer and broadcaster Michael Palin, actress Maureen Lipman, comedians Bill Paterson and Victoria Wood, and film critic Mark Kermode.

The survival of the Phoenix has relied to a large degree on the passion of local residents (including Maureen Lipman) to preserve it and fight off plans of developers. Today the cinema is owned by the Phoenix Cinema Trust Ltd, and in 1999 English Heritage recognised the historical and architectural significance of the Phoenix by granting it a Grade II listing. As a result the cinema is now protected from demolition and any further threats from developers.

The cinema has also starred in several feature films including most notably, Interview with the Vampire, The End of the Affair, Nine, Mr. Love and Nowhere Boy. It also features in the opening chapter of David Baddiel’s novel Whatever Love Means.

In 2010, in celebration of the cinema’s centenary, a section of the Phoenix was renovated to create the space for a new cafe-bar with balcony. Come here early and enjoy some excellent homemade fare, including soups, stews, mezze platters, cakes and real coffee – not to mention an outstanding range of beers and wines.

This North London picture palace of old has to be one of London’s most distinctive, and its audience one of the quietest. If you love cinema, you’ll undoubtedly fall in love this place.

The nearest tube station is East Finchley.

9Carlyle’s House

Number 24 Cheyne Row, Chelsea was the home of the historian and philosopher, Thomas Carlyle, and his wife Jane Welsh Carlyle. This couple enjoyed celebrity status in Victorian society and would entertain the likes of Charles Dickens, Alfred Lord Tennyson and George Elliot. The house, a Georgian terraced property dates from 1708 and sits in one of London’s best preserved early eighteenth century streets.

Comprising four floors, the house is now owned by the National Trust and has been kept as it would have been when the Carlyles lived here with their servant and pet dog, Nero.

Much of the original furniture, books, paintings and personal possessions of the couple have been tracked down and re-housed here, and one can gain a real feel for what a typical middle class house in Victorian London would have looked and felt like.

Carlyle spent much time trying to soundproof his study to protect his ears from the commotion of street criers, organ grinders and Italian ice-cream sellers. For in Carlyle’s day this was an unfashionable and not particularly desirable part of London. How times have changed. It was from this room that he penned his now famous history of the French Revolution, the first chapter of which was inadvertently tossed onto the fire by John Stuart Mill’s maid. Undeterred, Carlyle simply took up his quill and rewrote it.

In their time here, the Carlyles managed to get through as many as 32 maids; one of whom was an alcoholic and on one occasion (one imagines the last) collapsed in a drunken stupor in such a way as to block the front door. Another maid apparently went into labour in the China room.

Step down one floor and you’ll find yourself on the floor of Thomas Carlyle’s bedroom though this is now the custodian’s residence. Step down to the first floor and you’ll discover Jane’s bedroom and the drawing room/library. Below this on the ground floor is the parlour, and below this in the basement is the kitchen.

The small walled garden is as it would have been in the Carlyles’ day with a fig tree that still produces fruit.

This charmingly preserved house is open every day from 11am – 5pm from early March to late October.

[:en]London has no shortage of museums, galleries and sites of interest for the tourist, but there are many lesser known haunts that are well worth seeking out if you really want to experience a significant if little known part of this city’s colourful past. These are those little gems that are only familiar to the locals and are entirely missed by the hordes of tourists who visit London every year.

1The Clink

Ignore the popular and sensationalist London Dungeon which is no more than a gory Madame Tussauds and instead, head for The Clink Museum nearby in Clink Street. This small establishment is built on the original site of London’s oldest prison. Known as The Clink, this dubious establishment began life way back in 1144. At that time the area was known for its brothels, bars, bull-baiting and theatres, and The Clink, which was owned by the Bishop of Winchester, was London’s attempt to curb the local excesses.

Originally there were two prisons here: one for men and the other for women. And the Clink would undoubtedly have provided the bishop with a very satisfactory income from regulating the brothels and the resulting fines and prison sentences meted out. Indeed, the brothels were closed, reopened and moved over the years, and brought a constant stream of prisoners to the Clink’s doors.

By and large, prisoners were appallingly treated by their gaolers, who were themselves very poorly paid. Though if you or your associates outside had money, you could pay the gaolers to make your stay here more bearable. So to supplement their income, gaolers would hire out rooms, bedding and candles. They’d even accept payments for fitting lighter irons or removing them altogether. If you were unfortunate enough to be one of the penniless prisoners, you’d have to beg and sell anything you possessed including your clothes just to pay for food.

Here you’ll learn much about the area’s history and have the opportunity to handle original artefacts including some fairly questionable torture devices.

There is also a rather spooky side to the museum, as there have been an unusually high number of reported paranormal incidents occurring on the premises. These have ranged from the sighting of figures walking through walls to doors opening and closing and glasses inexplicably smashing. Who knows? You may come closer to history than you were anticipating.

No visit to London would be complete without a visit to this unique and fascinating museum.

[irp posts=”790″ name=”Top 10 Sehenswürdigkeiten in London”]2The Cheshire Cheese public house

While Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese public house at 145 Fleet Street may not be the oldest pub in London, there has been a pub on this site since 1538. During the Great Fire of London in 1666 the pub was burnt down but rebuilt shortly afterwards. Unlike other pubs which survived the fire because they were built from stone, this one was constructed primarily from wood. However, much of its internal wood panelling today is almost certainly 19th century though its vaulted cellars are thought to have belonged to a 13th century Carmelite monastery.

Despite its lack of natural light, the pub has a great deal of natural charm, which is enhanced further during the winter months by a roaring open fire.

Needless to say, the Cheshire Cheese has countless literary associations. Among its regulars have been such esteemed luminaries as Oliver Goldsmith, Mark Twain, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, G.K.Chesterton, Dr Samuel Johnson and Charles Dickens. Dickens, in fact, alludes to the pub in A tale of Two Cities when his character Charles Darnay is taken for a meal in Fleet Street and led “up a covered way, into a tavern… where Charles Darnay was soon recruiting his strength with a good plain dinner and good wine.”

In 1890 a group of London based poets – the Rhymers Club founded by W.B.Yeats and Ernest Rhys used the Cheshire Cheese as a regular dining club from which they produced two anthologies of poems in 1892 and 1894.

If you appreciate your English literature, come here and soak up the atmosphere. While you’re at it, order yourself a well-deserved pint.

3The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret

Located high up in the garret of St Thomas’s Church is one of the oldest surviving operating theatres beautifully preserved as a museum. There isn’t much known about the origins of the operating theatre other than the fact that in 1820 a herb garret was installed here on the original site of St Thomas’ Hospital. It is believed that the garret was used by the hospital’s apothecary to store medicinal herbs, and the following year a section of the herb garret was converted into an operating theatre. The original female surgical ward at St Thomas’ Hospital was situated adjacent to the herb garret in the building next-door – hence this rather bizarre and lofty location.

Before this time, operations would have been carried out on the ward. Quite what other patients might have made of this, one can only surmise. The patients here would all have been women. They would also have been poor. The wealthy were operated on at home – often on the kitchen table. In those days, surgeons had little in the way to dull a patient’s pain besides alcohol, opiates, and later on, ether and chloroform. Otherwise the surgeon relied entirely on his swift technique. Good surgeons would have carried out amputations in less than a minute.

The seating around the theatre would have been occupied by students. Being on public display may not have been dignified for the poor patients but it was the only way to receive treatment from some of London’s finest surgeons without having to pay for it. This said, many paid for it with their life, since there was no real understanding of infections and an alarming lack of hygiene. Many, of course, also died simply from the shock and trauma.

It wasn’t until 1859 when Florence Nightingale set up her nursing school at St Thomas’ that she persuaded the powers to be to move the hospital to a new site and sell the land to the Charing Cross Railway Company. So in 1862 the hospital moved to its current site at Lambeth and the operating theatre was closed up and forgotten about until 1957 when builders discovered it by chance when carrying out work to the eaves.

Besides seeing this fascinating operating theatre as it would have looked in its heyday, you can also browse the herb garret where herbs would have been stored and cured by the hospital’s apothecary. And if you’re not too squeamish, examine the fascinating display of

gruesome medical instruments employed in the days before real scientific knowledge. The Old Operating Theatre and Herb Garret can be found at 9 Saint Thomas Street, Southwark SE1 9RY.

4Keats House

The poet, John Keats lived at this charming Regency house in the leafy and salubrious London suburb of Hampstead from 1818 to 1820. It is where he penned perhaps his most famous and well-loved poem ‘Ode to a Nightingale’. It is also here that he fell desperately in love with Fanny Brawne, the girl next door. In 1820, due to ill health, Keats was advised to recuperate in Italy. Tragically, he was never to return to his beloved Hampstead and Fanny Brawne. Instead his health took a drastic turn for the worse in Rome where he died at the tender age of just 25 from tuberculosis.

Today Keats House is a small museum dedicated to the works of John Keats as well as poetry in general. Thanks to a Lottery Heritage Grant, the house has been very sensitively restored, and much care has been taken to refurbish the property to the reflect as closely as possible the way it would have appeared when Keats lived here. Alongside the house, the garden has also been replanted and designed to reflect the Regency period. There is, however, one specimen that has remained in place: a mulberry tree, which is thought to date back to the 17th century, so Keats would almost certainly have seen it.

Born in 1795, John Keats was writing poetry from the age of 18. But it was his friend, Charles Cowden Clarke who persuaded him to abandon his profession as an apothecary surgeon and pursue his natural talent. Influenced by Shakespeare and Milton, Keats was to become one of the most prominent poets of the English Romantic movement alongside Byron and Shelley.

Among the artefacts on display in the house are the engagement ring that Keats offered Fanny Brawne and his death mask.

Come here with a copy of John Keats’ poems, take in the house and garden, and prepare to be moved.

1The Secret Garden, Regents Park

Otherwise known as the Garden of St John’s Lodge, this little piece of manicured tranquillity is well worth seeking out. Its whereabouts isn’t widely known since its presence isn’t well advertised – hence the moniker: Secret Garden.

Head for the Inner Circle and its junction with Chester Road. The entrance, which is discreet (so keep your eyes peeled), leads you through a pergola walk which in turn brings you out into a lovely circular garden, the focus point of which is a large pond with the statues of Hylas and the Nymph. To your left is a glorious sunken lawn spread out before the splendid facade of St John’s Lodge. To the right is an arbour; step through this and you’ll discover the secluded oval garden in which you may care to take a seat. From here you can wander into yet another spherical garden though this one with its circle of lime trees around a stone urn is somewhat smaller.

These well tended gardens are a delight, and what makes them extra special is the fact that they are tucked away and out of sight. So on those balmy summer afternoons when Regents Park can be heaving with families, you can slip through the pergola and have this corner of paradise to yourself.

St John’s Lodge was built in 1819 and was privately owned up until 1916 when it was used as a hospital and later by the London University. Today St John’s Lodge is a private residence owned by the Sultan of Brunei.

The gardens were laid out in 1888 by Robert Weir Schultz for the 3rd Marquess of Bute and remain pretty much as they were then.

6The Soane Museum

Sir John Soane was a neo-classical architect with a remarkable penchant for acquiring paintings, drawings and antiquities on a mind-boggling scale. Indeed, his collection grew so incredibly large that he had to purchase several houses next door to accommodate his treasures. He began at number 12 Lincoln’s Inn Field in 1792. By 1806 he had bought number 13 next door. And by 1823 he had purchased number 14. During Soane’s lifetime, the house was established as a museum by a Private Act of Parliament.

Sadly, this became a legal necessity because Sir John’s legal heir, his son George, was by all accounts a thoroughly unpleasant character who refused to work, was constantly in debt and had written scathing pieces about his own father in the Sunday newspapers. So to stop his son laying claim to his property following his death, Soane senior set about disinheriting his son via a private Act in order to “reverse the fundamental laws of hereditary succession.”

As Soane’s business and personal wealth grew, he was able to purchase items that would have been at home in the British Museum. Such pieces include the alabaster Egyptian sarcophagus of Seti I, which he bought in 1824 for the princely sum of £2,000. Once the piece had been installed, Soane threw a three day party for 890 guests, including the Prime Minister, Robert Jenkinson, Robert Peel and the artist J.M.W. Turner. Other fascinating exhibits of ancient antiquity to be seen here include Greek and Roman bronzes, mosaics, vases and Roman glass.

In addition to the antiquities are the countless plaster models of statues and the paintings including four by Canaletto, twelve by Hogarth, one by Watteau, three by his good friend J. M. W. Turner, and one by Joshua Reynolds.

Then, of course, there is his own personal legacy: his extraordinary body of work represented by no fewer than 30,000 architectural drawings and 251 architectural models. Most of the drawings have been bound into 37 handsome volumes, and the remainder have been framed and adorn the walls. 118 of the models are for Soane’s own buildings; 44 of which relate to his work for the Bank of England.

What makes this museum so unique is the fact that it isn’t a museum in the conventional sense. This is first and foremost a home in which its remarkable owner was able to indulge his passion for collecting. The rooms, which are fascinating and impressive in themselves, tell us much more about Sir John Soane than any dry text could possibly attempt.

For anyone with an interest in art, architecture and civilization, this place is a must, but be warned, once through these doors you could well find yourself spending a great deal longer here than you might have expected. Such is the draw of the place.

7Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Lincoln’s Inn

Step out of the Soane Museum back into Lincoln’s Inn Fields. This is London’s largest public square and was originally laid out in the 1630s. It takes its name from the inns of court next door and the oldest building to be found here is Lindsey House occupying number 59-60, which dates back to 1640 and was designed by Inigo Jones. Its close proximity to Linclon’s Inn has over the centuries attracted several law firms to ply their trade here. The solicitors Farrer & Co set up their business in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1790 and remain here to this day. Among their prestigious clients is Queen Elizabeth II.

Make your way through to Lincloln’s Inn and you’ll be entering a world that will appear Dickensian. Established way back in 1489, this became the seat of legal learning. Today there are in fact four inns of court in London from which barristers practise. Lincoln’s Inn is arguably the most attractive and interesting of them all. Indeed, besides being able to spot barristers in their natural setting sporting their archaic wigs and gowns, you may very well spot a film crew filming a period piece or an English legal drama amid these attractively cobbled streets.

Lincoln’s Inn comprises three exquisite squares, the Old Hall, dating back to 1489, the Chapel, the Great Hall and Library, and the Gatehouse, which dates back to 1521.

Lincoln’s Inn is situated in Holborn, across the road from the Royal Courts of Justice. The nearest tube station is Chancery Lane.

8The Phoenix Cinema, East Finchley

The Phoenix Cinema is London’s oldest working cinema. Built in 1910, it opened its doors in 1912 as the East Finchley Picturedrome. The first film to be screened here was a documentary about the ill-fated Titanic which had sunk that very same year. Having changed hands and undergone various architectural changes over the years, its unique barrel vaulted ceiling has remained intact along with its 1938 Art Deco panels. Its patrons include film directors Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, writer and broadcaster Michael Palin, actress Maureen Lipman, comedians Bill Paterson and Victoria Wood, and film critic Mark Kermode.

The survival of the Phoenix has relied to a large degree on the passion of local residents (including Maureen Lipman) to preserve it and fight off plans of developers. Today the cinema is owned by the Phoenix Cinema Trust Ltd, and in 1999 English Heritage recognised the historical and architectural significance of the Phoenix by granting it a Grade II listing. As a result the cinema is now protected from demolition and any further threats from developers.

The cinema has also starred in several feature films including most notably, Interview with the Vampire, The End of the Affair, Nine, Mr. Love and Nowhere Boy. It also features in the opening chapter of David Baddiel’s novel Whatever Love Means.

In 2010, in celebration of the cinema’s centenary, a section of the Phoenix was renovated to create the space for a new cafe-bar with balcony. Come here early and enjoy some excellent homemade fare, including soups, stews, mezze platters, cakes and real coffee – not to mention an outstanding range of beers and wines.

This North London picture palace of old has to be one of London’s most distinctive, and its audience one of the quietest. If you love cinema, you’ll undoubtedly fall in love this place.

The nearest tube station is East Finchley.

9Carlyle’s House

Number 24 Cheyne Row, Chelsea was the home of the historian and philosopher, Thomas Carlyle, and his wife Jane Welsh Carlyle. This couple enjoyed celebrity status in Victorian society and would entertain the likes of Charles Dickens, Alfred Lord Tennyson and George Elliot. The house, a Georgian terraced property dates from 1708 and sits in one of London’s best preserved early eighteenth century streets.

Comprising four floors, the house is now owned by the National Trust and has been kept as it would have been when the Carlyles lived here with their servant and pet dog, Nero.

Much of the original furniture, books, paintings and personal possessions of the couple have been tracked down and re-housed here, and one can gain a real feel for what a typical middle class house in Victorian London would have looked and felt like.

Carlyle spent much time trying to soundproof his study to protect his ears from the commotion of street criers, organ grinders and Italian ice-cream sellers. For in Carlyle’s day this was an unfashionable and not particularly desirable part of London. How times have changed. It was from this room that he penned his now famous history of the French Revolution, the first chapter of which was inadvertently tossed onto the fire by John Stuart Mill’s maid. Undeterred, Carlyle simply took up his quill and rewrote it.

In their time here, the Carlyles managed to get through as many as 32 maids; one of whom was an alcoholic and on one occasion (one imagines the last) collapsed in a drunken stupor in such a way as to block the front door. Another maid apparently went into labour in the China room.

Step down one floor and you’ll find yourself on the floor of Thomas Carlyle’s bedroom though this is now the custodian’s residence. Step down to the first floor and you’ll discover Jane’s bedroom and the drawing room/library. Below this on the ground floor is the parlour, and below this in the basement is the kitchen.

The small walled garden is as it would have been in the Carlyles’ day with a fig tree that still produces fruit.

This charmingly preserved house is open every day from 11am – 5pm from early March to late October.